Originally published by A Voice For Choice Advocacy on July 10, 2025.

EDITOR’S SUMMARY: What if the key to recharging your brain isn’t a new app or supplement—but simply stepping back from the constant buzz? Unplug, slow down, and explore the surprising power of a dopamine reset. From the science behind your brain’s reward system to simple, meaningful ways to reclaim calm and focus, it’s less about deprivation and more about rediscovery. What if you could separate what fuels you from what drains you? Here’s a guide to a quieter, clearer mind.

The last time you picked up your phone, which was likely a few seconds ago, you might have felt a tiny twinge of satisfaction from a text, a “see where your package is on the map,” or any of the slew of notifications that vie for your attention. That little rush of enjoyment? It’s rooted in dopamine—the neurotransmitter that keeps you coming back for more, reinforcing habits even when you’re not fully aware of them. This tiny chemical messenger has a hand in everything from ambition to movement. It’s most often described as a reward signal, providing a shot of pleasure for all kinds of reasons—from the “ding” of a new message to a touch from a loved one to the smell of your favorite food.

That said, pleasure is only part of dopamine’s story. The rest is far more complex—and sometimes uncomfortable. While dopamine fuels feelings of happiness and satisfaction, it can also lead to cravings, impulsive behavior, and difficulty finding satisfaction—making it a double-edged chemical in your brain. One of the most well-known experts in dopamine is Stanford psychiatrist Dr. Anna Lembke, author of the best-selling book “Dopamine Nation.” She contends that while dopamine does help you experience pleasure and gratification, its most important function may actually be its help with motivation.

It’s affiliated with movement, a key to achievement for many human goals–from survival of early humans to present-day life. For example, scientists studied dopamine-deficient mice against “normal” mice, and the dopamine-reduced mice chose the easier-to-get-to, less-preferred food as opposed to the normal mice who were compelled to make the effort to head over for the better food. Lembke also mentions a study where rats were similarly compared (dopamine-deprived vs. normal), and when researchers put the cheese a bit further away from the lower-dopamine rats, they didn’t have the drive to go the extra distance to get to it.

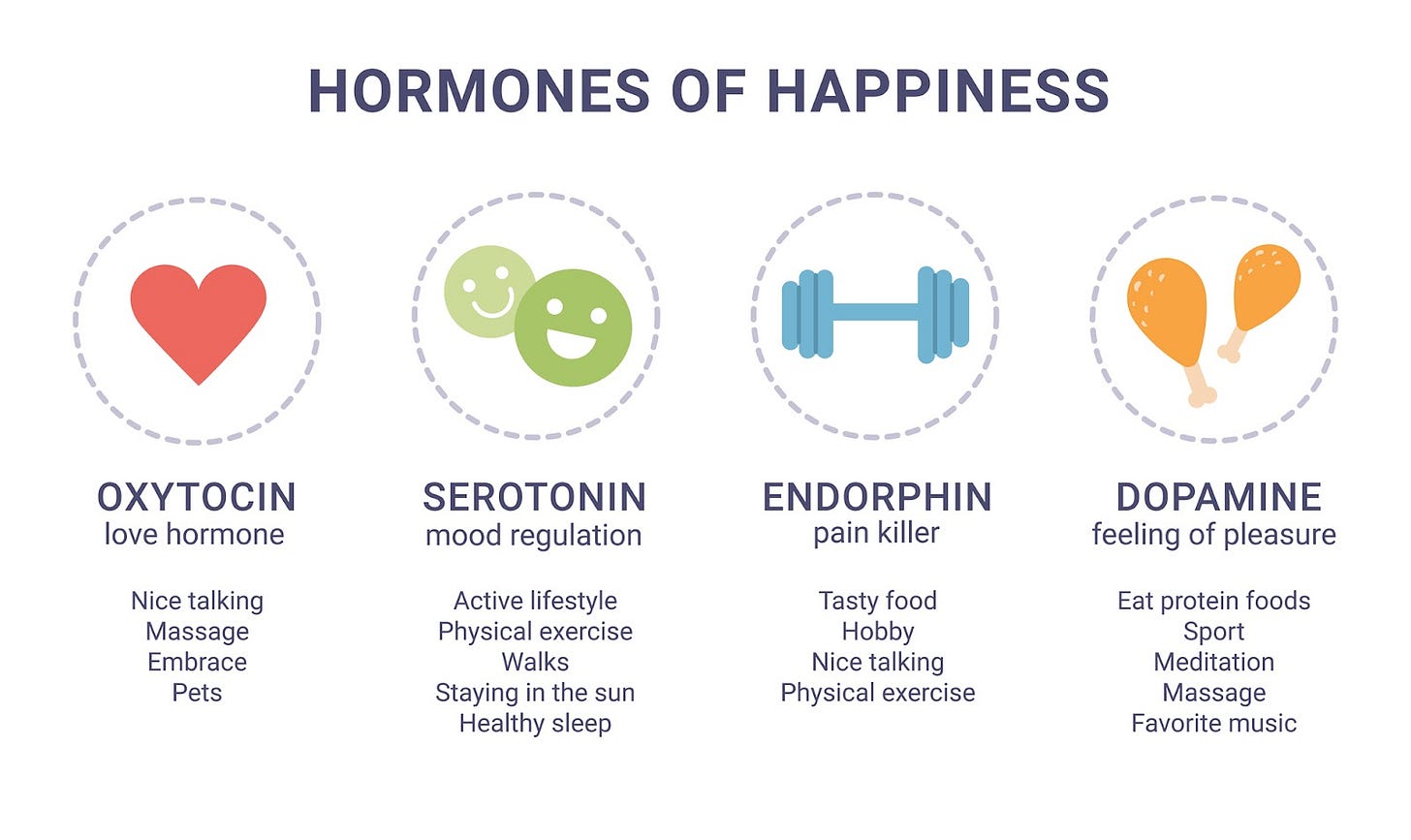

Dopamine plays a lead role—but it’s not a solo act. Serotonin, oxytocin, dopamine, and endorphins can act as both neurotransmitters and hormones, depending on where and how they function in the body. Though there’s no “Serotonin Nation” (yet), this is another chemical that plays a part in cognitive function. Serotonin is less about reward and has more to do with sleep, appetite, and mood regulation. For years, it was thought that if your mood was low, so were your serotonin levels. Hence the propensity of psychiatrists to prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to help the neurotransmitter’s ability to properly function in your brain. But a 2022 review, “Analysis: Depression is probably not caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain – new study,” dealt a shocking blow to psychiatry by deeming that serotonin levels were not responsible for depression and showed SSRIs to be only slightly more effective than a placebo (if at all).

Still, many mental health providers don’t concur with the blanket conclusion that antidepressants don’t work. They argue that the study shows the neural mechanisms of depression are more complex than first thought, and that there are many people for whom this mechanism does still work, even if scientists are unsure why. Oxytocin, often called the “bonding hormone,” plays a crucial role in social connection, trust, and emotional bonding—whether between partners, friends, or caregivers and their little ones. It’s a key player in feelings of warmth and empathy. Meanwhile, endorphins act as your body’s natural painkillers, released during exercise, laughter, or even spicy food to reduce discomfort and boost feelings of pleasure and euphoria.

Then there’s another neurological cohort: norepinephrine. This neurotransmitter (and hormone) affects your arousal, attention, and stress response. It also contributes to memory formation by strengthening neural connections, making it easier to form, catalogue, and recall memories. Another duty on norepinephrine’s resume is the management of your fight-or-flight response. Since it’s also known as noradrenaline, it’s no surprise that it works in conjunction with its relative, adrenaline. That’s the chemical that kicks up your heart rate during moments of stress—whether it’s a saber-toothed tiger or the sudden realization that you’re late for a meeting. Essentially, it takes a village…of neurotransmitters, working together, for ideal cognitive function. These chemicals don’t just have their own roles but work synergistically. As explained on the brain-centered site Neurolaunch:

“This interplay is particularly evident in the regulation of mood, cognition, and behavior. While serotonin is often considered the primary ‘mood regulator,’ both dopamine and norepinephrine contribute significantly to our emotional states. Dopamine’s role in motivation and reward-seeking behavior can profoundly impact mood, while norepinephrine’s effects on arousal and stress response also influence our emotional experiences.”

As for dopamine, your brain’s motivational spark plug, it can prompt you to feel alert, motivated, and happy—if briefly—and it’s been a key component in human survival. The modern concern with it lies in what scientists consider its intended design and what happens when it’s overstimulated by so many “triggers” in today’s high-tech, fast-paced world. In the grand scheme of human existence, smartphones and similar technologies are extremely new additions, and ones that your brain’s dopamine setup is ill-prepared to handle. In his podcast “Huberman Lab,” Dr. Andrew Huberman discusses with Dr. Anna Lembke how dopamine’s primary function is to support survival. But it was designed for your ancestors, when survival meant hunting for food, seeking water, and building shelter—tasks that required significant time and effort. That exertion was part of the process, and only after completing it did they get that satisfying burst of dopamine. In short, your ancestors had to work for their “hit”—and it was well-earned.

Today, namely courtesy of smartphones, you’re constantly bombarded with attention-grabbing notifications, ads, texts, videos, and access to seemingly infinite information. When engaging with your device—whether watching a video that’s quickly followed by another suggested one (thanks to some admittedly brilliant algorithms) or swiping left or right on a dating app—each small action delivers just a tiny bit of pleasure. Here’s the catch: in neuroscience, the effort you put in, even if minimal, is often labeled as “pain.” This doesn’t mean physical pain, but rather the mental or physical demand your brain perceives. Like much of your body, the dopamine system aims for homeostasis—a fancy word for balance—constantly weighing pleasure against pain..

Because pain and pleasure are processed in overlapping areas of the brain and use the same neurotransmitter systems, they function like a seesaw. As Dr. Anna Lembke describes it, if you keep piling on pleasure—video after video, swipe after swipe—without any real effort or “pain” to counter it, the seesaw tips out of balance. Eventually, your brain may lower its baseline level of dopamine in an attempt to restore equilibrium, which can leave you feeling flat, restless, or craving more stimulation just to feel normal again. This could be one reason why the more a person engages with social media or smartphones in general, there appears to be a correlation with depression. So as it turns out, you’re chronically releasing dopamine at a “tonic” rate—a steady, baseline level that helps regulate your mood and motivation over time. If you regularly expose yourself to substances or behaviors that repeatedly release large amounts of dopamine, it can change your baseline, lowering it to compensate. It’s simply more than your brain was designed to handle.

The other component of the dopamine system, aside from your steady release, or your ongoing level, is phasic transmission. Ali Abdaal, a doctor with training in psychology and neuroscience, details different ways phasic transmission can affect you. Using social media as an example, phasic transmission begins with a cue—for example the “ping” of a notification. After the cue comes the reward, but there are actually different types of payoffs. In his example, Abdaal says if you get that alert (“ding!”), your brain makes a prediction about what the benefit will be. He uses the example of the number of likes a photo or post receives. If you hear the ping and anticipate a certain number of likes and see you got more, that’s known as “prediction error.” Because it's a sudden delight, it gives you a burst of dopamine. Conversely, with a pretty accurate guess, prediction error is taken out of the equation because what you got was what you were expecting, so there’s little to no dopamine release. On the flip side, if you expect a certain number of likes and you end up with far fewer, you may experience a dip in dopamine.

Social media companies use these ins and outs of dopamine function to try to hook you or keep you scrolling longer. One of the most effective ways to do this is through intermittent surprises. Much like a slot machine where winning from time to time keeps you playing (and paying), these platforms know that the thrill of the unknown increases dopamine. So if you’re browsing and seeing predictable information, you may be turned off. But if they can interject something unexpected—maybe funny—the little bursts of dopamine could be enough to keep you scrolling. How does this lead to an altered dopamine baseline? If you use the substance or engage in the behavior too often, all those “phasic” hits start to change your tonic baseline. Then those phasic dopamine releases don’t feel as good as they used to because they’re not so different from your adjusted baseline.

As a result, there’s been a surge of interest in dopamine resets, fasts, or detoxes over the past few years. But dopamine isn’t the villain—it’s an essential brain chemical. In fact, it’s physically impossible to go without dopamine or rid yourself of it entirely, since your brain naturally produces it. Setting aside the semantics of “fasting” or “detoxing,” a more accurate description might be a dopamine reset. This consists of adjusting behaviors to try to reestablish that pain-pleasure balance, and there are different degrees of implementation that might appeal to you.

Lembke’s suggested reset involves choosing one thing that’s become problematic for you and removing it for 30 days. She tried this after realizing she was in an addictive relationship with romance novels. In her experience, most people feel better and come out of constant craving after about a month. She cautions you’ll feel worse before you feel better, but if you can get through the first 14 days, that’s usually when you begin to turn a corner. However, willpower alone doesn’t work, so it’s helpful to anticipate the desire before you’re in the throes of it, putting barriers between you and your “drug of choice.”

These might be physical, like locking something up, or time-based, like limiting how long you engage in the behavior if you’re not fully avoiding it during your reset. Also, it can help to be mindful of what 12-step recovery programs have long referred to as “HALT”: hungry, angry, lonely, tired—states that can trigger urges. Lembke highlights this framework as a simple but powerful way to check in with yourself before reaching for a dopamine-driven behavior. After your chosen period of abstaining from whatever your habit may be (while she recommends 30 days, even 5 or 10 can have some benefit), it’s best to slowly reintroduce what you’ve been avoiding to maintain the benefit of the exercise.

Similarly, in his book “Understanding the Heart: Surprising Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of Heart Disease—and Why It Matters,” Dr. Stephen Hussey proposes a less drastic—well, perhaps more drastic but shorter—dopamine fast. He suggests a one-day full “detox”—fasting not only from your phone (except for emergencies) but also from entertainment like TV, movies, and music, as well as exercise, and yes, food. Food is especially tricky because junk foods can trigger dopamine release due to their taste, while even foods considered healthy can naturally stimulate dopamine or boost its precursors. Bananas, eggs, and dark chocolate, to name a few, fall into this category. Of course, even thinking about tasty foods can result in a dopamine rush, so there’s only so much you can realistically do. Hussey doesn’t pretend this detox is an easy feat, but he asserts that “of all the things I do to increase my HRV, this has the biggest impact.” Heart rate variability (HRV) measures the variation in time between your heartbeats, and higher HRV is linked to better stress resilience and overall health.

One of the first proponents of dopamine resets was Dr. Cameron Sepah, a Silicon Valley psychologist. His approach may be more realistic for your lifestyle, as he advises starting a fast in a way that is minimally disruptive to your daily routine. Sepah’s suggestions are based on, or similar to, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, regarded as one of the most effective types of psychotherapy. He suggests one approach is simply to make it harder to access the stimulus you’re trying to avoid. So if your smartphone is taking over, put it in another room, or if possible, turn it off for a while. Another strategy he offers is doing an activity that doesn’t allow you to do the one you’re trying to avoid—Sepah uses the example of being unable to stress eat if you’re playing a sport.

Also within the category of stimulus control: website-blocking software for sites you’re trying to avoid, or even something as simple as setting your phone to grayscale or using an app like Minimalist Phone. These tools are designed to make your phone less appealing to use by muting the visual lure that’s designed to draw you in. If you’re not able to physically be away from your stimulus (for example, having to be online or near your phone for work, or being near tempting foods in the food service industry), there’s the CBT technique known as “exposure and response prevention.” This is more of a “sit with the feeling” approach. If you have an urge to engage with the thing you’re trying to refrain from, rather than grabbing your phone or the bag of cookies, sit with that impulse and notice the thoughts and feelings that arise. Sepah calls watching an impulse come and go “urge surfing.” Some addiction specialists suggest that if you can wait about 15 mins without giving in, the urge will often pass.

What to Do When You Step Back

If you decide to give one of the more intensive resets a try, how might you spend your time differently? Apparently, one of the few allowables on the Hussey plan is journaling. He occupies his fast with a pen and paper in his hammock in the woods of his backyard, writing and reflecting. Of course, not everyone has a hammock… or woods… or a backyard. Or the luxury of a day when you can actually lie back and just be in the midst of life. You might have kids running around or pets that need feeding or one of those job things. But even carving out a smaller amount of time to sit and “be” without reaching for the phone or a snack or entertainment of some kind could give your brain a bit of a refresh.

Though “mindfulness” is a vague, oft-overused term these days, mindful practices that require a slowdown, such as deep breathing, meditation, and body scans—where you slowly bring attention to different parts of your body—have resulted in improvements in dopamine regulation. Whether or not you feel its effects, taking a break from the world and enjoying a little silence can be a small gift to yourself. In the absence of constant sensory input, your brain has a chance to shift out of a reactive state. Silence has been shown to lower cortisol levels, reduce heart rate, and support parasympathetic nervous system activity—your body’s natural “rest and digest” mode. Without the usual stimuli triggering dopamine spikes, your system can begin to reset baseline levels, creating a more stable foundation for focus, mood, and decision-making.

All of this modern dopamine-triggering stimulation raises a question: could it be affecting you or your kids in other ways? With pleasure just a tap, swipe, or click away, it might explain why tolerance for frustration seems to be lower nowadays. In “Dopamine Nation,” Lembke contends that, collectively, people may be finding it harder to tolerate even minor discomforts—including you. She’s far from the only one who thinks this way. Popular psychologist Dr. Becky Kennedy shines a light on the value of frustration, calling it an inherent part of learning and growth. Kennedy advocates letting kids sit with frustration—even building it in intentionally if you’re in a privileged situation—so they learn how to tolerate it. While her advice is geared toward parents, it can just as easily apply to adults facing similar challenges.

The idea of letting yourself, or your kids, be bored isn’t just an (elderly voice) “in my day, we played with sticks, and we liked it” hand-me-down lecture. Being bored is actually important for creativity. While this applies to adults as well, it’s especially important for kids, whose imaginative abilities often flourish during childhood. If you’re handing your kids a device every time they experience a moment of boredom, think of that dopamine “scale” and what might happen in your child’s brain, or yours, if it’s constantly entertained. It’s worth considering the ideas and inventions they might miss out on—games and creations that won’t come to life if they don’t have the chance to sit with their own thoughts.

Regardless of how you decide to execute your own dopamine recalibration (admittedly less catchy-sounding than a “dopamine detox”), the process can be more effective with intentional tracking. Psychologist Dr. Susan Albers suggests keeping note of what seems to trigger the pull toward whatever you’re trying to go without. If you want to go even deeper, she encourages journaling by asking questions like these:

“Is it easy for me to walk away from this activity?”

“When I return to it, does it feel as pleasurable as before?”

“Is stepping away from it causing me noticeable anxiety or frustration?”

If the idea of a full reset feels like too much, you can try smaller “bites”—like doing activities that feel uncomfortable or are a bit of a stretch. Inviting pain—in a healthy, not destructive way—can help support the brain’s pain-pleasure balance. This might include physical discomfort, such as exercise or cold water immersion, or cognitive discomfort, like something intellectually or socially challenging.

It might be worth trying a dopamine fast with your family or a good friend. Of course, you can’t exactly text each other about how it’s going, but spending time in person, fully engaged with people you care about, is the kind of dopamine boost—through social bonding—that’s considered healthy. Whatever path you take, giving your brain a chance to calm down and find its rhythm again—even if you don’t go all-out for 30 days—is likely to offer some benefit, whether it’s renewed focus or simply a greater sense of peace. Sometimes, the most powerful reset isn’t about removing everything—it’s about noticing what you actually have, and what’s truly essential.

~

If you've found value in this article, please cross-post and restack it!

To support the research and health education of AVFC editorial, please consider making a donation today. Thank you.